Sunday 22nd January to Thursday 26th January 2017

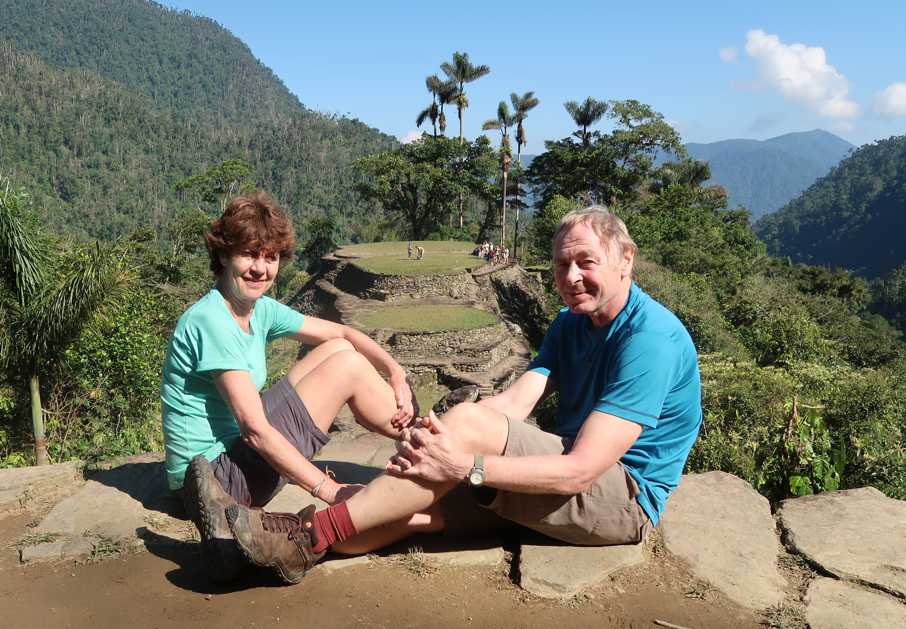

The five day trek to the Ciudad Perdida was tough but the compensation was the most beautiful, stunning scenery in the lush, dense, green jungle of the Sierra Nevada mountains, the indigenous people we passed on the way and finding out about their lives and history, and the Lost City itself which was remarkable. 1200 stone steps up to the site which stretches up the mountainside with numerous circular stone terraces and the mountains rising up all around. The group was beset by a number of problems including blisters, inflamed mosquito bites, knee pain and D&V but it felt a fantastic achievement to have done the trek.

The Ciudad Perdida, the Lost City high up in The Sierra Nevada in the north of the country, is Colombia’s Machu Picchu, but unlike Peru’s better known ancient, ruined city in the mountains there is only one way to get there, on foot, and as a result the Ciudad Perdida has many fewer visitors each year, about 8,000 in 2011 compared to the 5,000 who visit Machu Picchu every day in the peak season. It is also thought to be much older, founded in about 800AD, some 650 years earlier than Machu Picchu.

The 47km trek (there and back) passes through the land and villages of the indigenous tribes who have lived here for centuries and for whom the Ciudad Perdida is a sacred place. It must be done with one of four authorised tour companies taking either 4, 5 or 6 days depending on how quickly you want to do it. We decided to do the five day trek with Magic Tours, going at a slower pace as we were uncertain of our fitness and so that we could enjoy the countryside. Fellow cruisers Paul and 14 year old Lily from Delphinus, and Ian and Stephanie from Nautilus had arranged to join us. We had to carry everything we needed in backpacks, apart from food and bedding, and I had managed to get mine down to 3.5kg (excluding water): a couple of spare t-shirts, knickers and socks, long trousers and shirt for the evening, bathers, a silk sleeping bag liner and travel towel, mosquito repellent, camera and torch and that was about it. Hugh carried the bar of soap we shared as well as his own stuff.

We turned up at the offices of Magic Tours in Santa Marta on day one and it was then an hour’s drive out to the village of El Mamet at the start of the trail. After lunch our guide Nicolas and interpreter Abraham ran over the details of the trek before we headed off along the path.

We set off into farmland and after a gradual up and down track the path headed up steeply for two hours through spectacular scenery, green hills with areas cleared for cultivation, high mountain peaks around. Motorbikes and mule trains carrying provisions and gas bottles passed us, going to and fro along the trail to provide for the trekkers’ camps and the indigenous villages. At the top we stopped for a much needed rest and slices of watermelon. Those of us who had previously disliked watermelon – Hugh and Lily – decided it was quite delicious! As we continued the walk there was a wonderful stillness and quiet apart from the crickets and birdsong. A further more gentle climb up before a long, at times painful, steep descent down, crossing a stream over a wobbly bridge and on to the first camp, Casa Alfredo after our first day’s walk of 8.4km.

I was expecting to sleep in hammocks but was relieved to find we had bunk beds with mattresses, mosquito nets, pillows and blankets. There was a shower block at each camp with an icy cold shower, but at least we could wash the dirt and sweat of each day away – and it was highly refreshing. A cold beer tasted like nectar and supper of red fish, rice and salad was wonderful.

After supper our guide, the wonderfully enthusiastic and energetic Nicolas, explained how there used to be extensive coca plantations in the area, with FARC controlling the production of cocaine. In the 1970s the Colombian government allowed the US to aerially spray the land with chemicals to kill the coca bushes but in doing so the other crops grown by the indigenous farmers were also killed and the land poisoned. Since then it has mostly recovered and the farmers grow a large variety of crops as well as grazing cattle. They are permitted to grow up to 15 coca bushes, a rather dull and harmless looking shrub, for their own use. Although Colombia is again the world’s number one exporter of cocaine production here in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada is low.

I was so exhausted I was nodding off during his talk and we were in bed by 8pm, however I found it hard to sleep as it was so cold at night in the mountains. It was still dark when we woke at 5.30am to continue the trek before it got too hot to walk. After a breakfast of arepa with cheese, bread and jam, melon, pineapple and papaya, we set off as soon as it got light.

Further into the mountains the scenery became increasingly beautiful with green above, below and around us as we walked steadily uphill and the sun gradually rose over the top of the mountain opposite. We passed through a meadow of high, course grasses and ferns, orange trees laden with fruit, and crossed streams and rivers, removing our boots to wade across the deeper ones up to our knees, occasionally crossing over precarious-feeling suspension bridges.

We stopped at a Kogi village, a cluster of thatched huts, the women hidden away inside sewing the bags that they use – mochillas – made of woven wool or cotton. The children sucked on lollipops given by one of our group. Some of the men were herding cattle including a particularly splendid bull. I spotted one man chatting on his mobile phone using a solar panel to keep it recharged. Nicolas told us how the men carry dried coca leaves in their mochillas and chew the leaves, mixing them with pulverised sea shells collected from the Caribbean coast, which are crushed in their popora, a dried gourd. They dip a stick into the popora to extract the powdered lime which is mixed with the wad of coca leaves in their cheeks and chewed, the alkaline of the lime activating the alkaloids in the coca leaves. The mixture is mildly narcotic, helps them to think and expand their minds, to suppress hunger so that they can go for three days without eating or sleeping and to communicate with their gods or ancestors. The indigenous people of the Sierra Nevada are of four tribes: Kogi, Wiwa, Arhuaco and Kankuamo, who believe they are the descendants of the original Tayrona people. Although their way of living is largely unchanged over the centuries they have increasing contact with the outside world through healthcare provision, schooling and tourism. They wear white clothing which symbolises the purity of nature and the Arhuaco men wear white hats which represent the snowfields of the sacred peaks. The girls wear necklaces and the boys carry mochillas, but only when they reach 18 are the boys permitted to chew coca leaves. The women must pick the leaves but are only allowed to drink tea made from the leaves and not to chew them.

We explored the village feeling like intruders but were mostly ignored by the people living there who didn’t seem to mind us taking pictures. Along the track we would pass groups of indigenous people on their way to and fro who would sometimes respond to a friendly ‘hanchika’ – which I was taught was ‘hello’ in Kogi.

At the next lodge along the way we stopped for a swim in the river, very cold but refreshing after the heat of the day, then lunch. A chef and his assistant came along as part the tour group and would cook our meals, clear up and then run along the track to meet us at the next camp whilst we plodded along, strung out along the trail depending on our fitness or lack of it. We were with a group of 13, six cruisers and the others in their 20’s and early 30s. Chris and Connie, and Matheus and Catalina were students from Chile, Stephan from Holland, Abigail from Israel and Dora from Tunisia; a bright and interesting group of people all of whom spoke excellent English and Spanish.

After lunch it was another more strenuous hike initially two hours steeply up hill. I ran out of energy before the top and Nicolas carried my bag for the last ten minutes. Several slices of fresh pineapple and a chocolate bar later I felt able to go on although some other members of the group were starting to suffer with painful knees and Connie had her blistered feet bandaged up. She was carried by Nicolas across the deeper rivers and later in the trek gave up trying to wear her trainers, completing it in a much more comfortable pair of borrowed crocs. When we finally reached Camp Paradiso after walking 13.9 km that day I was completely exhausted.

Day three was the big day… the one when we finally reached the Lost City. We were up at 5am and after breakfast, leaving our backpacks at the camp, it was a short walk along a path by the river to the start of the 1200 steps up to the Ciudad Perdida. The narrow, uneven, stone steps wound steeply up the mountainside through the dense surrounding jungle and it was easy to imagine how they could have become overgrown and the way up to the city lost to the outside world for so many centuries, known only to a few of the indigenous people.

It took about half an hour to get to the top where there were the first of many circular terraces, of which there are maybe 240 in the Ciudad Perdida, stretching up the side of the mountain.

Nicolas explained more about the Lost City, which is known as Teyuna to the locals and considered a sacred place built near to the stars, and about the people who inhabited it. We explored the site which is much more extensive than expected. There was a wide staircase which leads up to a series of higher terraces with wonderful views of the surrounding mountains and jungle. At the top you could look down on the view – the one that appears in all the tourist publications.

The city is believed to have been built between the 9th and 14th centuries by the Tayrona tribes who then inhabited the region. There were thought to be around 2000 people living in the city at one time, farmers, artisans and metalworkers. It was largely abandoned in the 16th century following the Spanish conquest possibly due to diseases brought over by them such as smallpox and syphilis, although it might have continued to be used for sacred ceremonies. It remained undisturbed for over three hundred years, overgrown by jungle, until discovered by grave robbers in the 1970s who looted large quantities of pottery, gold and other artefacts. When these started to appear on the black market the government and archaeologists got wind of it and eventually one of the looters, Franky Rey, guided them to the site. For years it was considered unsafe to visit due to drug warfare and paramilitary activity in the area, in 2003 a group of tourists was kidnapped on their way to the Lost City and the site was shut down until 2005. The Colombian army now maintains a strong presence and there were soldiers camped out at the summit of the Lost City and at one of the camps we stopped in.

.

The people are very spiritual, particularly the Mamas – the priests or shaman of the tribes in the Sierra Nevada. They are selected at a young age and trained over 9 years by the elders during which time they live in a darkened cave. The mamas are consulted on important events, even before a tree is cut down. Today the people subsist in the mountains mainly on agriculture, growing banana, plantain, cacao, coffee, maize, beans, yucca, rice, avocado, papaya, guava, lemon, pineapple, mango and orange.

We spent around three hours in the city, before we descended slowly back down the 1200 steps and retraced the path we’d taken.

It seemed a long and tiring day’s walk back to where we were to spend our third night. Matheus had been feeling increasingly unwell, suffering from a nasty tummy upset, and that evening Ian and I went down with it too – apparently a common occurrence on this trek despite the care we had taken to drink only bottled or purified water. So we were glad of an easy fourth day when we had the morning off and stayed in the camp, Casa Mukake. Some of the group went swimming and I went back to bed and slept.

Nicolas had arranged for one of the indigenous people to come to talk to us. He was Santiago, a Wiwa, who had married a Kogui woman so had come to live with her tribe, it being a matriarchal society. He had brought his popora to show us and chewed and spat regularly. As they chew, some of the seashell mixed with spittle is used to coat the outside of the popora, which represents their thoughts, and so the popora grows in size.

After lunch we continued back along the path to the first camp we’d stayed in, arriving after walking for just 6.5km, although it felt like much further. We were just in time as the skies opened and the track turned into a muddy, slippery slide in the heavy rain.

We had a late start on the final day leaving at a very civilised 7.30am. I felt much better, stronger and more relaxed, striding out and not finding the final hill that we had to climb then descend nearly such a challenge as when we had tackled it on our first day. There was a great feeling of bonding in the group as we took our time to enjoy the countryside and the wonderful views.

It was only another 8 km back to El Mamay where we’d started and where we celebrated with a cold beer, feeling a huge sense of achievement. I was relieved to be back, not the least as all my socks were damp, my clothes filthy and I’m sure I stank despite the daily cold showers.

12 Comments

George

March 2, 2017 - 1:56 pmOh what an amazing tale, Annie. I am very impressed with your adventures.

George

March 2, 2017 - 1:57 pmFab photos too!!

annie

March 2, 2017 - 3:56 pmThanks so much George xxxx

Steve

March 2, 2017 - 2:08 pmWowwwww!

annie

March 2, 2017 - 3:56 pmor owwwww! as my legs were saying 😉 xx

Sam Lucas

March 2, 2017 - 7:52 pmLooks like you are having a great time! I’m very jealous, this is one of the activities I would have liked to have done when I was there, but ran out of time. Looks incredible!

If you haven’t left the area yet and haven’t done it already. I really enjoyed Tayrona and Taganga. Taganga is a 30min drive outside of Santa Marta (the bus was easy). From here you can go scuba diving in coral reefs.

I hope you enjoy the next leg of your journey and see you soon!

annie

March 4, 2017 - 12:06 pmHi Sam, lovely to hear from you. We spent a day in Tayrona (see previous posts) but didn’t manage to get to Taganga – just so many wonderful places to see in Colombia xx

Karen Rochester

March 2, 2017 - 11:37 pmIt sounds like a totally fantastic journey to take…in every sense. Loving seeing the pictures too – both the incredible scenery and you both looking so well. Xxx

annie

March 4, 2017 - 12:04 pmThanks Karen. It was an amazing trek and glad the pain didn’t show in our faces 😉 xx

The Jetski

March 3, 2017 - 1:41 amWhat an achievement. You seem to be extracting so much from this adventure. Fascinating write up as always.

annie

March 4, 2017 - 12:02 pmThanks Mr J xx

Alieu

April 28, 2017 - 9:04 pmThis is amazing.you guys are great.