I have been back in the Seychelles for over a week now after just over two months at home in Bristol. Hugh had arrived two weeks earlier than me, getting the engine etc sorted, and Vega was beautifully clean and tidy when I arrived – that didn’t last long! Ahead of us, in October, is the passage that I’m most fearful of, the Mozambique Channel, and I know I’m not alone here. But in the meantime we hope to do some cruising around the beautiful islands of the Seychelles.

As anyone who has been following this blog will know I’m very much a fair weather sailor and don’t particularly enjoy long passages at sea, especially in bad weather and rough seas, and we had plenty of those on the trip here from Chagos. I can become quite fearful, especially at night, one of my greatest fears being Hugh going overboard in bad weather, not being able to rescue him and being left alone on the boat. Although we have AIS tracking devices inside our lifejackets it would be very difficult to find him at night in rough seas and even more difficult to get him back on board, especially if he was injured or exhausted.

It has taken me a long time to write this blog, partly as I found it difficult to reread my diary of the passage. This has definitely been the worst passage of the whole voyage so far. Apart from two days of enjoyable sailing the rest of the 12 days was mostly unpleasant and at times quite terrifying. The wind was unpredictable, no wind, too much wind, sometimes from the west when we wanted to sail west, 12 knots one minute then 25+ knots the next, meaning were constantly furling the genoa or dropping the mainsail, or unfurling and raising sails, only to find we had too much or too little sail up. Frequent squalls with heavy rain made conditions very unpleasant. The seas were often choppy and chaotic, which caused the boat to roll and slow down, although occasionally gentler seas allowed us to speed up. Hugh was a hero tackling most of the sailing in bad conditions whilst I often became unhappy, anxious and afraid, which I’m not proud of. So many times I’ve promised myself and him: that’s it, I’m not getting back on that boat. But somehow I’m still here.

So at the risk of being far too long and drawn out here is the story of our worst passage so far.

Wednesday 11th to Monday 23rd May 2022

The 1000 mile sail from Chagos to the Seychelles looked easy. You just head south west to about latitude 7 degrees south to pick up the SE trade winds, then a pleasant sail west in gentle winds and calm seas until you get near to the Seychelles, then northwest to Mahé, the largest island, to check in at the capital, Victoria. Easy, it should take us 8 or 9 days based on the weather forecasts we’d been seeing. I was even rather looking forward to it and had plans about baking bread and cakes, fishing for tuna and mahi mahi, making delicious meals etc….. How wrong I was.

For many yachties crossing the Indian Ocean, and particularly those heading down the Mozambique Channel to South Africa, the go-to person for weather forecasting and passage planning is Des Cason. Des has sailed this route many times but now spends his retirement, at home in S Africa, giving advice to cruisers for free.

As we were settling down to a cold beer on our first night in Chagos, Hugh read out the latest email from Des ‘Allow me to dispel some myths about the SE trades. Unlike the Atlantic and Pacific the Indian Ocean has peculiarities which make it a very hostile ocean…’. We laughingly, and it turns out foolishly, composed a jokey email along the lines of ‘Annie is wondering is it too late to ship the boat home or where she can get a flight home from now?’ We never sent it. We really should have listened more attentively to Des!

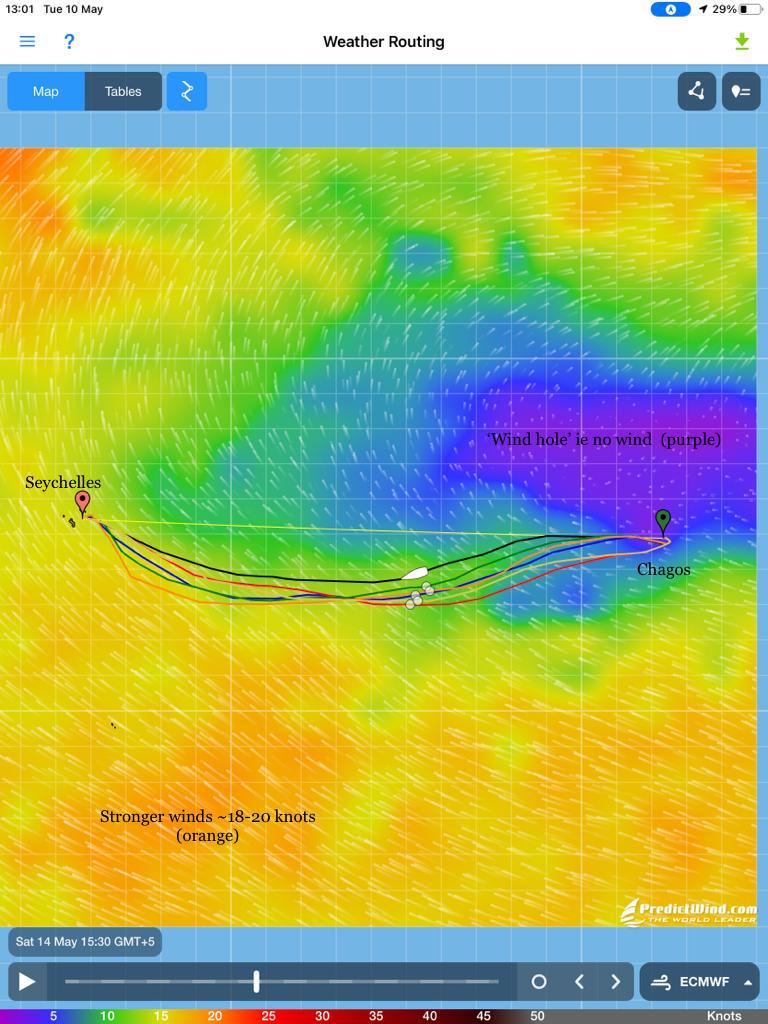

We subscribe to a weather forecasting and passage planning app called PredictWind, and get daily forecasts and updates at sea using our satellite system, with suggested routes to take. The forecasts are based on a number of different GRIB files (compressed weather forecasting data) produced by various weather forecasting centres such as the U.K. Met Office.

The forecast above was done on May 10th, the day before we left Chagos. It shows suggested routes we could take and where we would be by May 14th, four days ahead. As you can see it predicts there will no longer be any wind at Chagos by the 14th, which is why we decided to leave when we did. But as Des puts it: ‘Weather forecasting is “black art” so can only convey what the gribs show’.

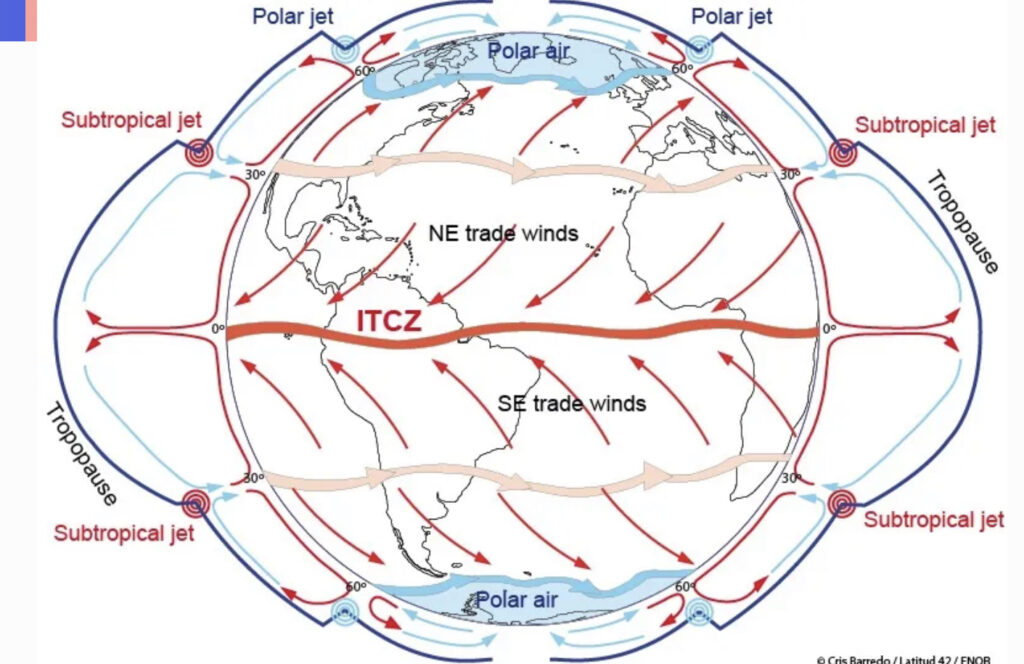

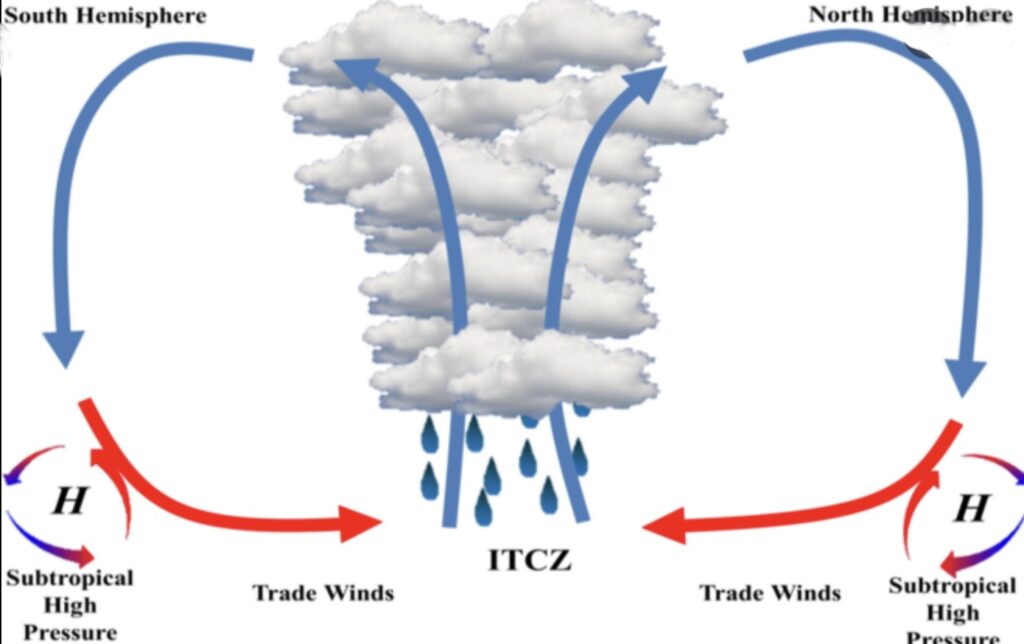

Around the equator is the ITCZ (the inter-tropical convergence zone) between the trade winds of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. An area known by sailors as the doldrums because of the monotonous windless weather but also an area renowned for thunderstorms, squalls and rain showers. The ITCZ tends to move north or south depending on the time of year and this year it was unseasonably far south, meaning we needed to sail further south than usual to pick up the SE trade winds. From Des ‘The only predictable thing on the edge of the ITCZ is its unpredictability.’

Des again…. ‘The Indian Ocean has an extremely bad reputation for very good reasons. In this transition period between the NE and SE trade winds….severe wind conditions are invariably due to squalls and thunder storms.But unfortunately that comes with the territory. Just the nature of the beast.’

With the wind forecast to die off around Chagos in two or three days time and with our concerns about the worn bearing in the propellor shaft meaning we didn’t want to use the engine, we needed to get going. We regretfully headed off on the Wednesday, all ready for an 8 or 9 day sail, as prepared as we could be. Meals had been cooked for the first few days at sea, everything was stowed, the check-list checked and life-jackets and safety equipment on hand.

Our first two days at sea the winds were as hoped, around 10 to 12 knots, mainly from the SE, and we made good progress south west on a smooth sea aiming to get down to 7 degrees south of the equator to pick up the SE trade winds. Des warned us that ‘If you stay on 6S you will run into the southern edge of the wind hole developing. This area of no wind could expand and would strongly recommend you aim to get below 7S by Saturday. No threats apart from the wind hole. Have a great day. Des’. I always feel rather lethargic and queasy for the first few days at sea as my body adjusts to the motion of the boat and to disturbed sleep as we take turns on watch overnight.

On our second night at sea, soon after midnight, Hugh spotted a boobie sitting right at the top of the mast, taking a rather wobbly rest from flying. He was worried it might damage the instrument that measures wind direction and speed that is located at the top of the mast. He tried shining a torch at the bird, switching the nav lights, that are also up there, on and off, shouting and blasting the fog horn at it. Nothing would budge it and I certainly wasn’t going to be hauled up the mast at sea, at 1am. After that our wind direction instrument did indeed stop working consistently.

The next day the wind dropped and the seas became bigger causing the boat to roll unpleasantly from side to side. We poled out the staysail with the genoa, which took an age to achieve, but with a sail on either side of the boat we could sail better with the wind behind us. We were still making reasonable progress. And then around midnight the squalls hit.

In a squall the wind might suddenly increase from a gentle 5-10 knots to 20, 30 knots or even more, with gusts of over 35 knots, often accompanied by torrential rain. With too much sail up then they can quickly overpower the boat causing it to lean dangerously to one side, tear the sails or even capsize it. During the day you can see low, dark rain clouds approaching from any direction but on a dark night they can be hard to spot without radar. With one coming your way you need to get the sail reduced, lifejacket on, don wet weather gear and shut all the windows and hatches before everything inside the boat gets soaked. With frequent squalls, heavy rain and a rolly sea that next day we were both becoming exhausted.

On the morning of day 4 the wind came round from the west, the direction we needed to go, and Hugh took the helm, steering, as the wind and seas were so difficult. We were forced to sail SSE, further south but heading away from the Seychelles, and the crew became increasingly despondent. We sent daily emails to Des and on his advice continued to head towards 8 degrees south, hoping to reach the SE trade winds. Hugh spent much of the time on deck battling the wind and rain, whilst I made him hot meals – potato wedges with tuna, cheese, sweetcorn and mayonnaise (surprisingly good on a foul night!) In the early hours, as the wind gradually died, we took the sails down and just drifted in no wind and light rain, turning all the instruments off to conserve battery power.

On day 5 we had an email from Des ‘you have arrived at the top edge of the SE trades and have survived the tiger bearing his teeth.’ The morning felt brighter, the sea flatter with big, widely spaced rollers coming from the east, and the wind started to come in from the southeast, lightly at first then increasing to 15 knots. We reefed the genoa and enjoyed the feeling that we could at last start to make progress although it was dispiriting to realise that by noon of day 5 we had got exactly zero miles nearer to the Seychelles in the previous 24 hours. At midday the squalls started coming in again and the wind backed to the northeast. We tried to sail NW but made little progress west and so tacked, now heading SW again, desperately trying to get further west to make up the distance we’d lost. Later that afternoon the wind settled and we had easier sailing, with a quieter night.

It was highly entertaining that evening at dusk watching the red footed boobies coming in to land on the smooth shiny surface of our solar panel then jostling for position, trying to get a grip with their webbed feet. They squawked at any newcomers, trying to dislodge them and I got so fed up with their squabbling I prodded them all off. They gradually returned and eventually there were six perched in a row, who settled down to sleep for the night after some preening, head under wings. In the early morning light it was like returning home to find the teenagers had had a party whilst you were away. The deck, awning, solar panel and railings all around were covered in bird poo. That was the end of a free overnight ride for the boobies.

The following day it promised to be much easier sailing and I decided to make a cake. By mid morning the squalls were back with heavy rain and a confused sea rolling Vega from side to side. The pineapple upside down cake lived up to its name and ended up sliding into the sink as the boat rolled. Fortunately the sink was empty so i could salvage most of it. I began to feel increasingly depressed, apathetic, scared and anxious, every minute was hard to bear. We still had 625nm to go and we were making dreadfully slow progress. Hugh was in the cockpit dealing with the sailing in the heavy rain, winds and chaotic sea. I made him lunch then had a weep and gave myself a pep talk to stop being so miserable.

It was a long day as we continued our slow progress west, with the GRIB files all suggesting we get further south despite the long row of squalls all the way. When the wind eventually dropped we had a cup of tea and played scrabble, and took turns at napping. When a huge rogue wave hit Vega on the side everything went flying, including the tea. Overnight the wind came in from the NE, the sea became calmer and we had some good sailing in 12 to 18 knots of wind. All the hopeful boobie hitchhikers got pushed off the railings and solar panel.

Day 7 was a stressful day of putting up and taking down sails, poling out the staysail to try to get further west now the wind had veered to the SE then the S. The winds we were getting seemed to bear little relationship to the ones predicted by PredictWind, or to Des’s forecasts. After reporting our overnight progress Des would reply along the lines of ‘the wind hole in the process of moving spawned a small cell of low pressure and with clockwise rotation generated some contrary local winds’. Hmmm.

Hugh was getting frustrated with me and we weren’t communicating well. I became more anxious and fearful again, but as the weather and the sailing improved I started to feel better. We tackled the communication issue, realising we needed to share sailing and sail plans more. After a pleasant evening of sailing on a flatter sea we started our usual watch system of 3 hours on, 3 hours in bed. I was so tired that I napped during my watch, coming up on deck every 10-15 minutes to check the weather, the sails and that there weren’t any other vessels around – very unlikely so far from land and well away from any shipping lanes. Around midnight there was another squall on radar so I woke Hugh to get the mainsail down. Then at 0300hrs he decided to raise the mainsail which meant him leaving the safety of the cockpit and going forward in the rough sea, something I always hate especially in the dark.

Day 8 and we should have been nearing Mahé by now, according to our original 9 day passage plan, but we still had over 450 miles to go. I made coffee and left the cafetière on top of the gimbled stove to brew. The cafetière slid and tipped over, pouring boiling hot coffee over the top of my left thigh, leaving a nasty blistering scald. As Hugh helpfully reminded me, coffee should be brewed at a temperature of 87 degrees and not boiling. Health and Safely procedures on Vega are continually under review.

That afternoon the sea was gentle in light winds and we put up the cruising chute until dusk, then sailed with just the genoa in the dark. We tend not to use the big sail overnight in case the wind suddenly comes up and we’re overpowered. We had a great sail until around 0100hrs, when I watched on the radar as a squall slowly approached from starboard, hoping it would miss us. Too late, as the wind suddenly increased to over 20 knots, I woke Hugh who came up on deck wearing nothing but his lifejacket, and we got the large genoa reefed. After the squall had passed the sky cleared and it turned out to be a beautiful night with a waning full moon, sailing in 12-14 knots of wind on a slight sea. I gradually let out the genoa and had a wonderful sail… the first time I’d really enjoyed it on this passage!

There had been, of course, other compensations for the darker times. Some beautiful sunsets and sunrises at sea. A full moon which lit the sea for most of the night when it wasn’t stormy. The planets strung out in a row in the hours between the moon setting and the sun rising. The sea birds which we see hundreds of miles from land, sometimes solitary but often in pairs or a group of 10 or 20, swooping low over the water hunting for fish, so elegant in flight and, at night, circling the boat hoping for somewhere to rest.

On passage we’d also been keeping in touch by email with family, and friends at home and on other sailing boats. My son Alex’s partner Sarah had been in hospital for two days in possible labour, but was then sent home. I hoped the baby would hold on until we got home (he did and Charlie was born on June 17th). Endorphin and Hecla had just left Gan, heading towards Chagos, and friends on Nahoa were on their way towards the Seychelles directly from the Maldives and having their own difficulties.

The following morning was bright, warm and sunny. We were heading in the right direction at last, doing 5+ knots in light winds, sailing well with the cruising chute up most of the day. An email from Des…. ‘Glad the Indian Ocean for a change is showing some mercy – strange!’.

Normally we share the cooking on passage, but this time I did most of it, freeing Hugh up to deal with weather forecasting and passage planning and with most of the worse weather. We discussed sail plans several times a day, especially before dusk to ensure we had hopefully anticipated any difficult conditions after dark. Mostly we sailed just with the genoa, which easy to furl quickly, but also at times with a reefed mainsail and a poled out staysail which works well when the wind is almost directly behind us. We had the cruising chute up a couple of times until dark clouds approaching warned of stronger winds and time to take the big sail down.

For supper that night we had tuna salad with lentils, with Christmas pudding and cream, eaten in the cockpit as the sun set, listening to the Who’s greatest hits. Later more squalls passed through and at one point I crawled to the bow to untangle the cruising chute sheets which had got tangled in the furled genoa. A boobie had decided to sleep on top of the satellite dome that night and would not be persuaded to move.

Day 10 at sea and we continued to sail well in gentle conditions. I made a granny cake and had a shower on deck (although it emptied the larger of our two water tanks). By the afternoon conditions had deteriorated again with the wind backing to NNE, increasing to over 25 knots with heavy rain and a rough sea. Hugh stayed in the cockpit dealing with the sailing whilst I made a sweet potato and chickpea curry. Overnight the wind settled a bit allowing us to take turns at sleeping. In the early hours, on his watch, Hugh nodded off and, as the boat rolled, he fell forward onto the cockpit table, giving him a hard blow and a nasty graze on his forehead.

By day 11 we were still progressing far too slowly towards our destination in dismal, cloudy, wet conditions in a choppy sea. In the afternoon a pod of large dolphins, possibly small whales, passed at a distance and later we watched a flock of small, black and white seabirds swooping low over the waves, occasionally diving under the water to catch small, silver fish. I had tried at times putting out the fishing line but never had a bite, probably as we were just going too slowly. We spent an hour untangling the cruising chute which had managed to twist back on itself, finally succeeded and had an hour of gentle sailing with it up.

Although we were at last approaching the Seychelles we still had to negotiate the large area of shallows that surround it. This meant heading north for 35 miles before turning west directly towards Mahé, the largest island. It was another bad night with heavy rain and squalls. Hugh nobly stayed up most of the night, in wet weather gear and life jacket, dealing with one squall after the next, jibing as necessary, whilst I cowered down below, in the dry, providing food and cups of tea as required, but spent a lot of the time napping or trying to maintain a zen-like calm. I don’t think he got any sleep at all that night.

In the morning there was a heavy sky and drizzle, the sea a dark steely grey with white horses and rollers. We sailed slowly with a reefed genoa only. Hugh slept most of the morning whilst I sat in the cockpit, staring at the sea which just looked immense and terrifying.

From Des: Dear Hugh and Annie …. What you have experienced so far is uncomfortable but not fatal. Unfortunately the Mozambique channel is a different animal but that is a fight for a different day. Have a safe run into Victoria and expect some turbulent seas across the shallow banks. Best wishes and safe night. Des’

As we turned west towards Mahé there were dark grey seas and storm clouds, but we were now less than 100nm from Victoria, the capital of Mahé. We approached where the ocean depth abruptly rises from 2000m to 50m and had anticipated rough seas here but, thankfully, as we crossed the shelf, it was an anticlimax. Overnight the heavy cloud started to clear and the sea became less choppy. In the early hours as I slept Hugh had ‘some of the best cruising on this passage’ in a slight sea and steady 14 knots of wind.

When I woke on day 13 of our passage the lights of Mahé were in the distance, with the outline of the mountains, their peaks covered in cloud. Nearer to land we could make out the densely wooded mountain slopes with small, colourful houses dotted around, then some wind farms and large tuna fishing trawlers.

Approaching Victoria we called Port Control for permission to enter the channel into the outer harbour. A few hours after dropping anchor in the quarantine anchorage, with just time to clear up a bit down below, officials from Customs and Health came on board to clear us into the country. After that we motored slowly in to Eden Marina. The Seychelles is beautiful, as expected.

The final word from Des:

‘Dearest Hugh and Annie Thanks for the good news and extremely happy you got in safely. The Indian Ocean must be going soft letting you have some decent sailing right at the end!! …….

The Mozambique channel is a very dangerous place to tackle if you have not done the home work and have a handle on what you are dealing with.

Have a great time and look forward to hearing from you in due course.

Best wishes

Des’

14 Comments

Tom Hutchison

August 18, 2022 - 10:42 amWhat an amazing read Annie. You guys are truly brave. Mozambique Channel next sounds terrifying. Take every care. Tom

annie

August 19, 2022 - 6:25 amHi Tom. Yes I’m rather dreading it but hopefully with good weather forecasting we’ll survive it 😫 xx

Judy

August 18, 2022 - 10:51 amAnnie.. 😮 💨🌪🌪⚡️ 😦😩😫😵💫🫣😭😨😰🤢 🙏

Thank you for removing any vestige of envy that I have been feeling …😂😍

Thinking of you often xxx all our love and admiration to our hero saint Hugh😇 xx ps it’s all his fault ..🥰

🪐🌕🌎✨🧜♀️🦈🐋🦭🐬🐬🐠🐟🐡🐙🦑🦞🦀🐚 🧑🏻⚖️🕊🦜🏖🏝⛱.. bits of envy lurking…

🛒🛒 reminder of being safe at home 😂

Xxx

annie

August 19, 2022 - 6:26 am😄😂😂😂😂😘😘😘

George Evans

August 18, 2022 - 3:46 pmDear Annie. No envy at all from me. It was so hard to even read this post. I can’t imagine the process of living through the experience. I am so pleased you are both safe (minor injuries only). Enjoy your rest and recuperate well. George

annie

August 19, 2022 - 6:19 amThanks George. Fully recovered now xx

Gerard

August 18, 2022 - 7:55 pmI was frightened just reading your blog. The only laugh was to imagine Hugh at the helm with nothing on but a life jacket. You are a very brave couple never far from my thoughts.

Gerard

annie

August 19, 2022 - 6:17 am😂😂😂 I never managed to take a picture you’ll be glad to hear, but it was quite comical! xx

Paul Bayley

August 19, 2022 - 6:32 pmGosh I went out on a very slow boat in Kefalonia it was very calm but felt quite unwell and got sun stroke so I take my hat off to you both it sounds very frightening indeed. Your writing brings it all to life.

Best wishes

annie

August 19, 2022 - 7:04 pmThanks So much Paul. Kefalonia sound lovely though, much more sensible xx

Annie Sparkes

August 20, 2022 - 9:32 amBloody hell girl that was scary even to read. I’m amazed at your on board cooking abilities lol.

annie

August 21, 2022 - 8:58 amThe important thing when cooking is a wide-legged stance to brace against the rolling motion of the boat. I’m hoping that we can get the freezer working on the next passage so it will just be reheating frozen meals! xx

Clare

September 1, 2022 - 5:28 amOMG – I think you both managed amazing well considering how difficult the weather was. I would have been truly terrified! Good luck on your next stage

Lots of love Clare & Ju x

annie

October 9, 2022 - 12:44 pmThank you Clare & Julian x